Indecent Exposure Is a Crime. Indecent Leadership Is a Choice.

From Forks to Sequim, residents are cleaning up needles while officials defend policies that created the mess

This week’s Social Media Saturday isn’t about politics—it’s about what residents are posting, photographing, and living with in real time. From drug paraphernalia scattered across hospital-owned property in Forks to indecent exposure in a Sequim shopping center parking lot, the gap between policy rhetoric and street-level reality has never been clearer.

“Harm Reduction” Arrives in Forks

A post circulating recently out of Forks shows what many residents say is the inevitable result of Clallam County’s harm-reduction experiment reaching the West End: used needles, tourniquets, burned furniture, and drug debris scattered across a wooded property locally known as “the Burn.”

Community members have already conducted cleanups. They’re organizing again.

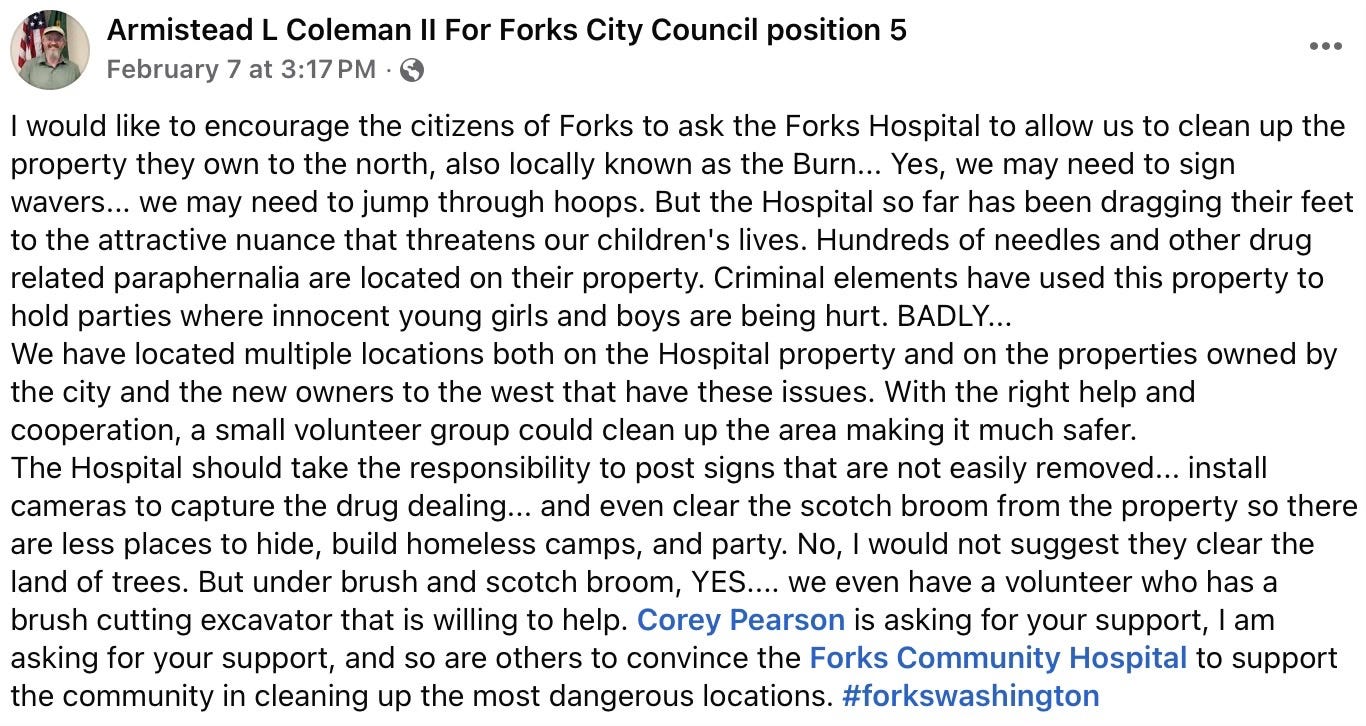

One widely shared message called on Forks Community Hospital to allow volunteers access to hospital-owned property north of town:

Hundreds of needles and other drug-related paraphernalia are located on their property. Criminal elements have used this property to hold parties where innocent young girls and boys are being hurt. BADLY...

Residents say the solution isn’t radical. It’s basic stewardship:

Allow volunteers to clean the property.

Post permanent signage.

Install cameras to deter drug dealing.

Remove scotch broom and dense underbrush that conceal camps and illegal activity.

A volunteer has even offered a brush-cutting excavator.

The request isn’t confrontational. It’s collaborative.

But the frustration is unmistakable: How did we get here?

Clallam County leaders promote harm reduction as “compassion.” On the ground, residents see needles in the woods.

Congratulations, Clallam County. The policy has nearly reached the coast.

Scanner Report Roundup: What Residents Are Seeing

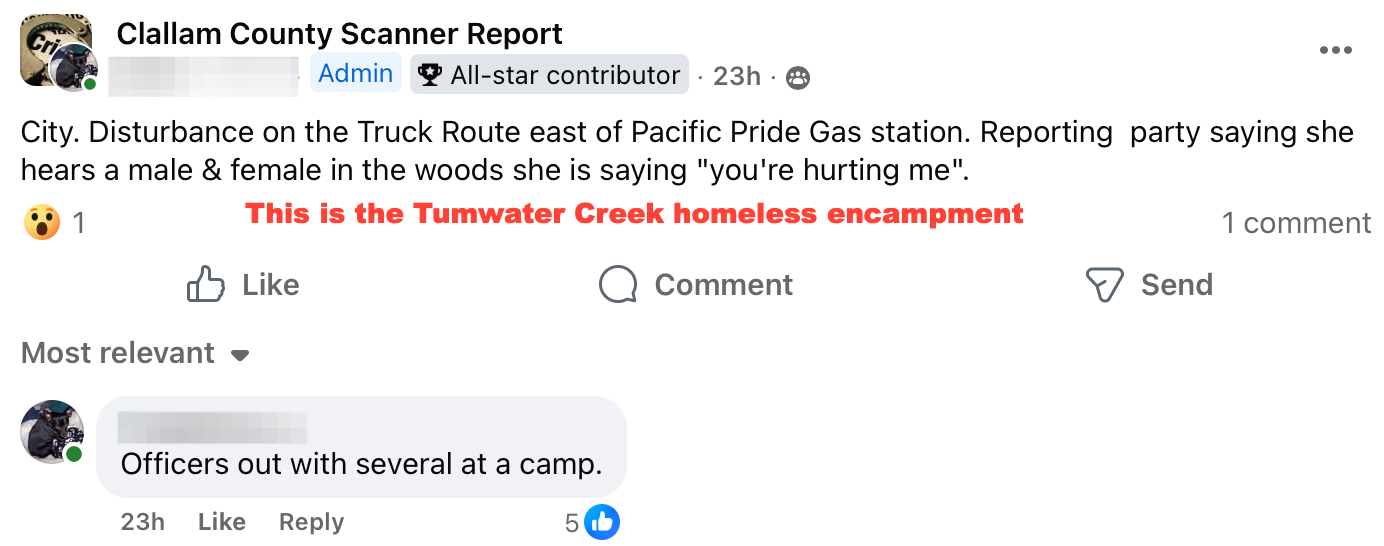

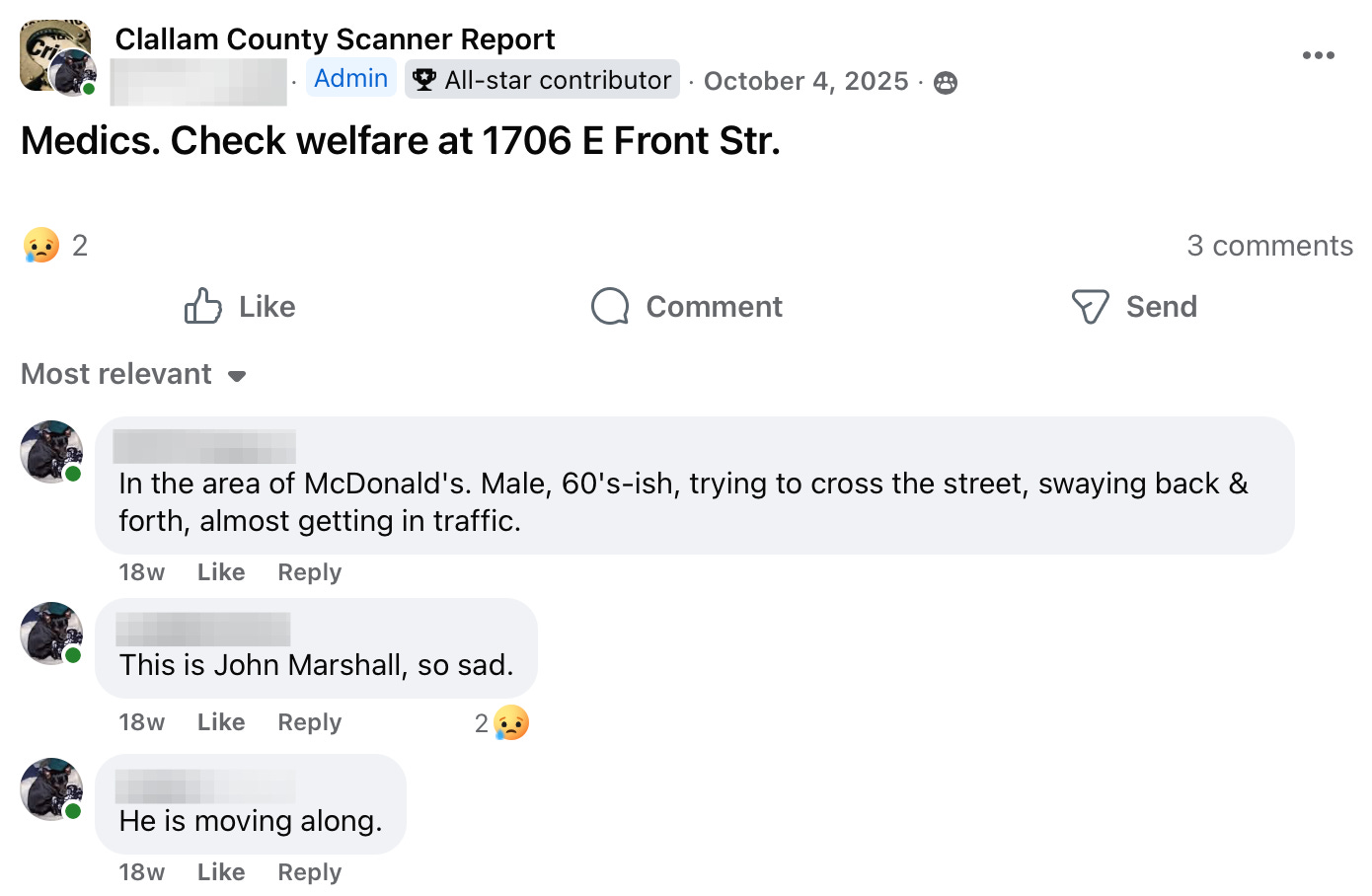

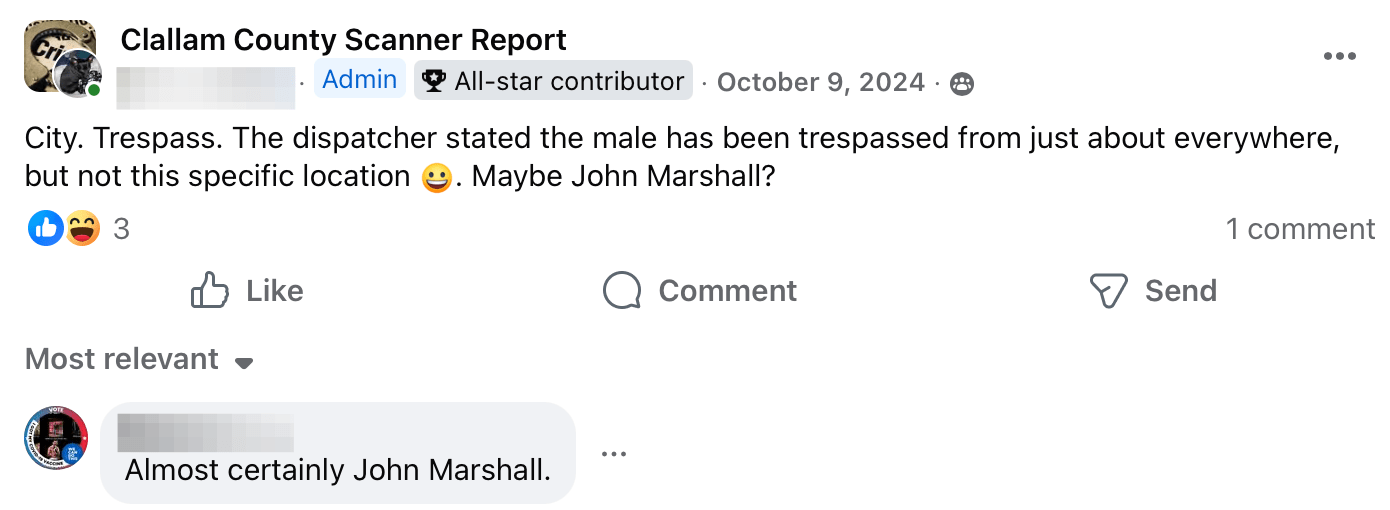

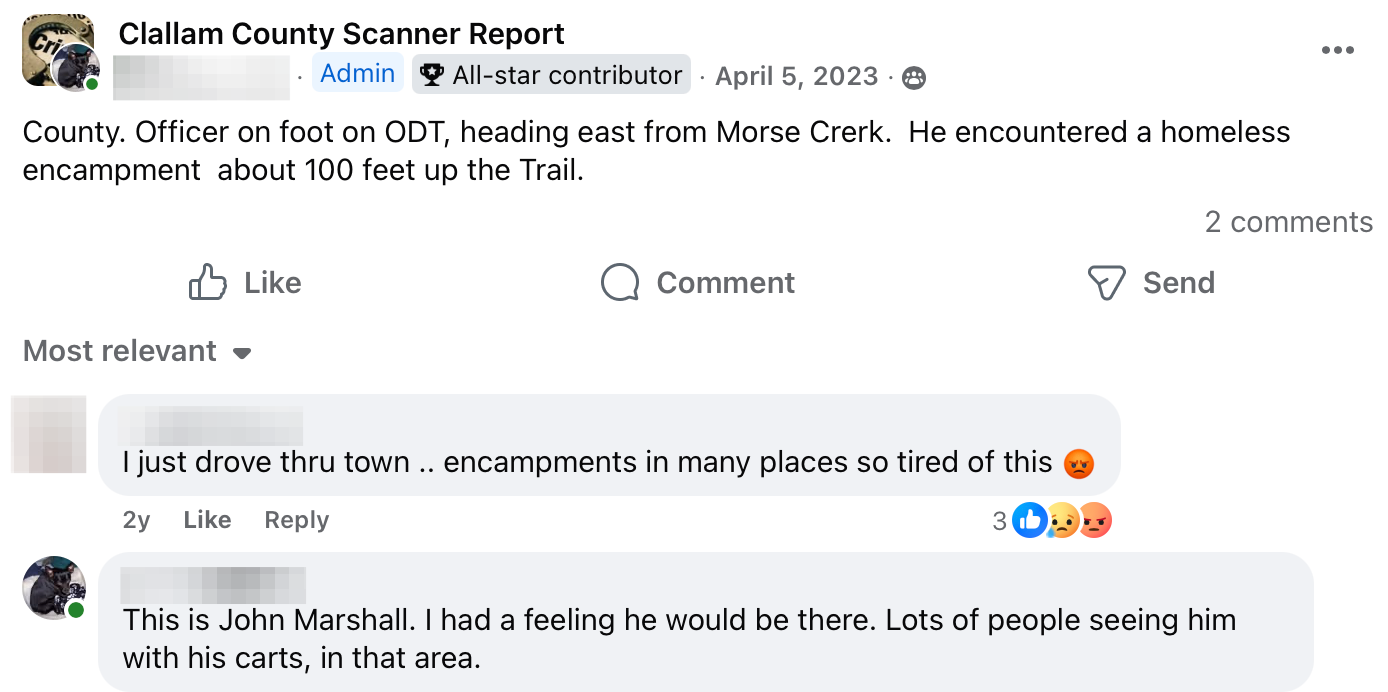

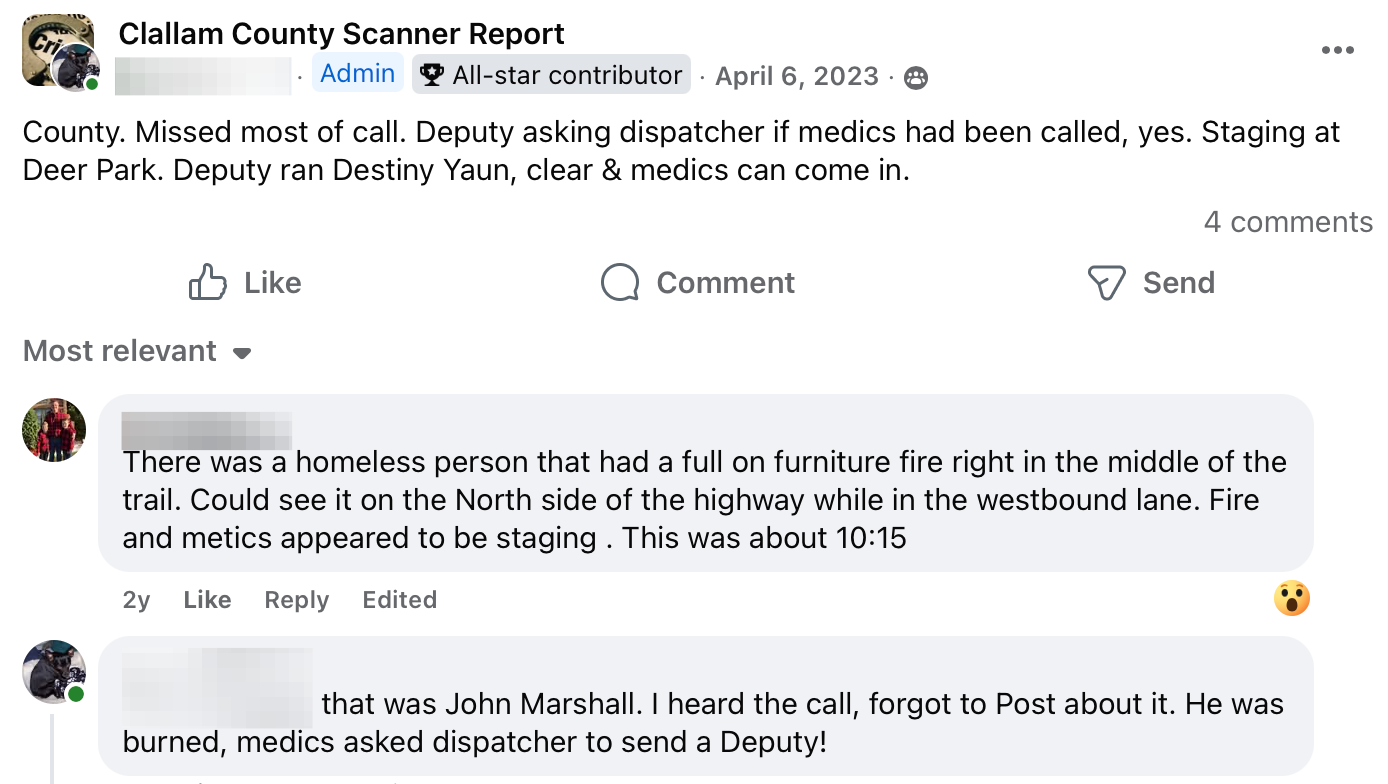

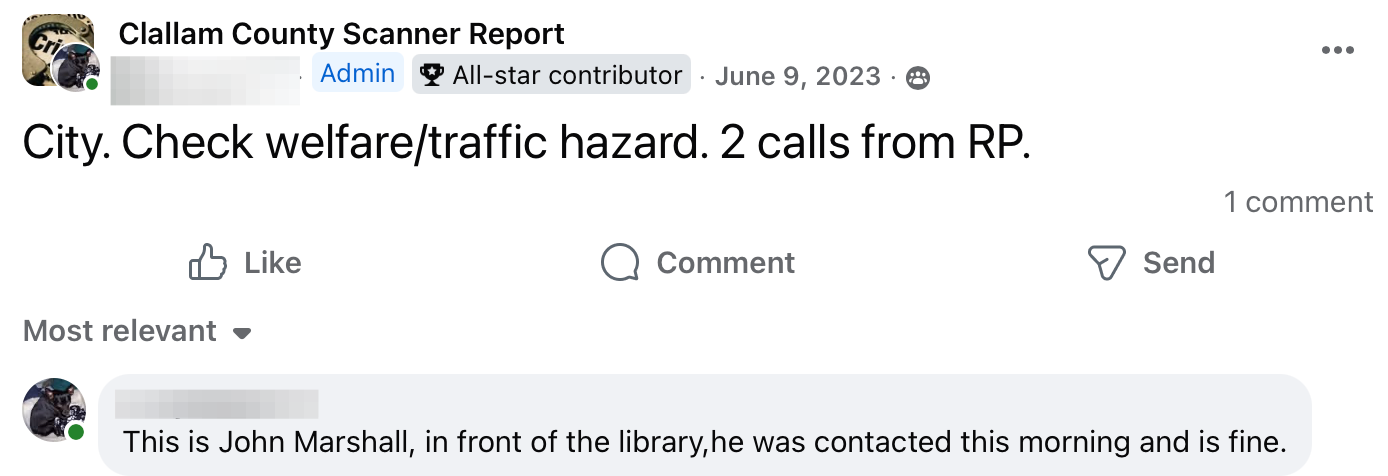

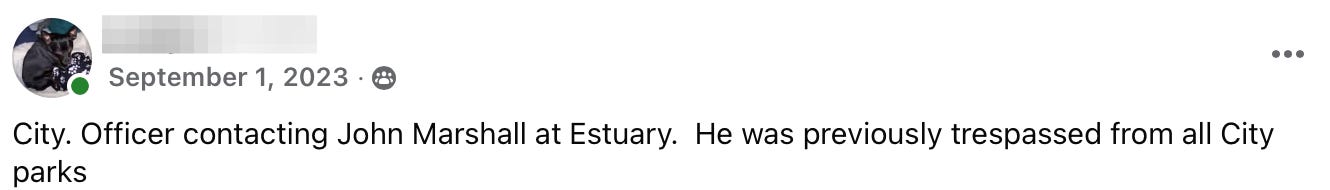

The Clallam County Scanner Report page continues to chronicle a steady stream of disturbances, trespasses, public intoxication, and property issues tied to unmanaged street-level disorder.

These aren’t partisan posts. They’re time-stamped dispatches from people watching their communities change in real time.

The question residents keep asking is simple:

If we are spending millions on harm reduction, housing-first, outreach, and supplies—including drug paraphernalia—why are the same names showing up over and over?

Which brings us to Sequim.

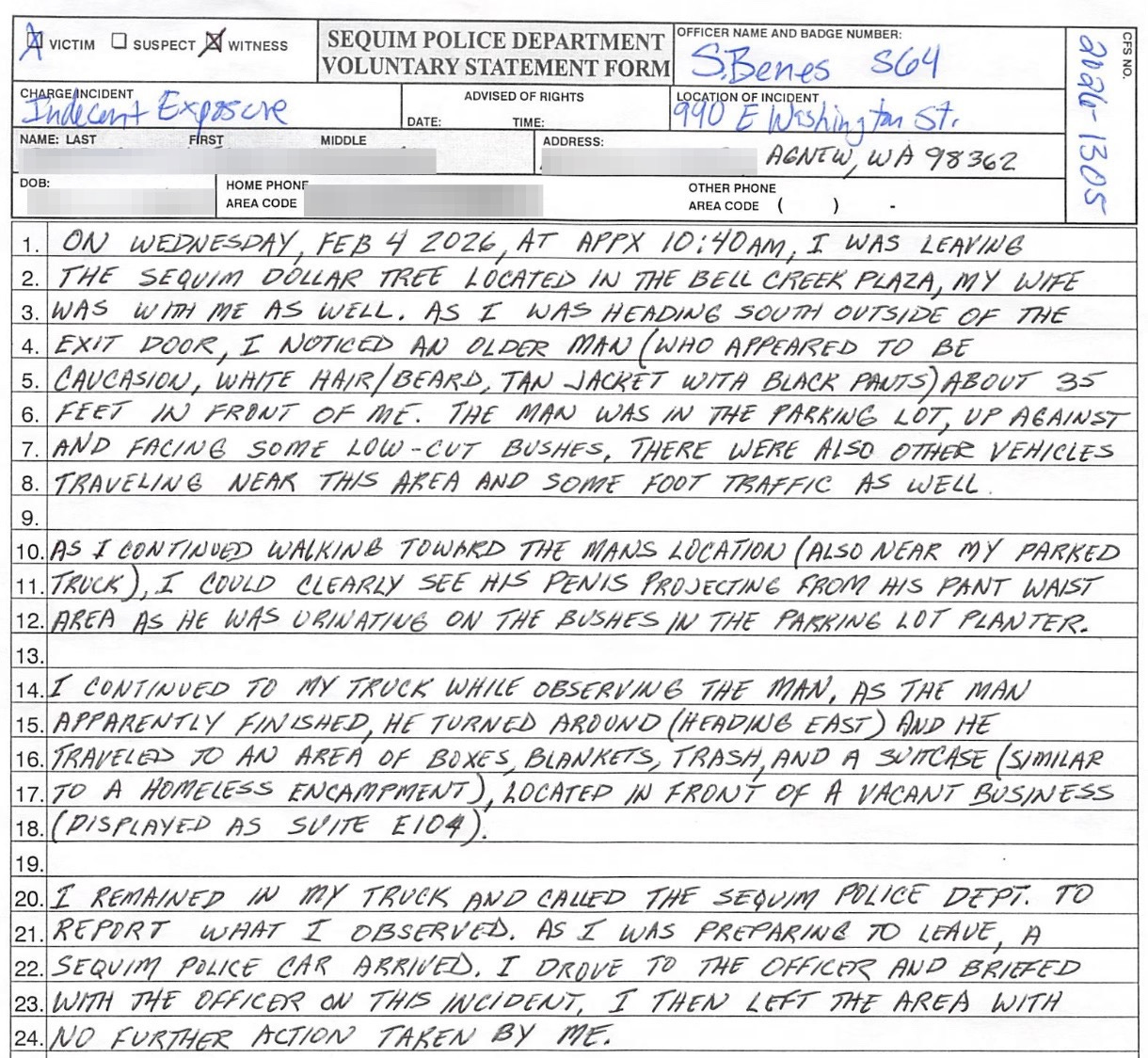

Sequim: Indecent Exposure

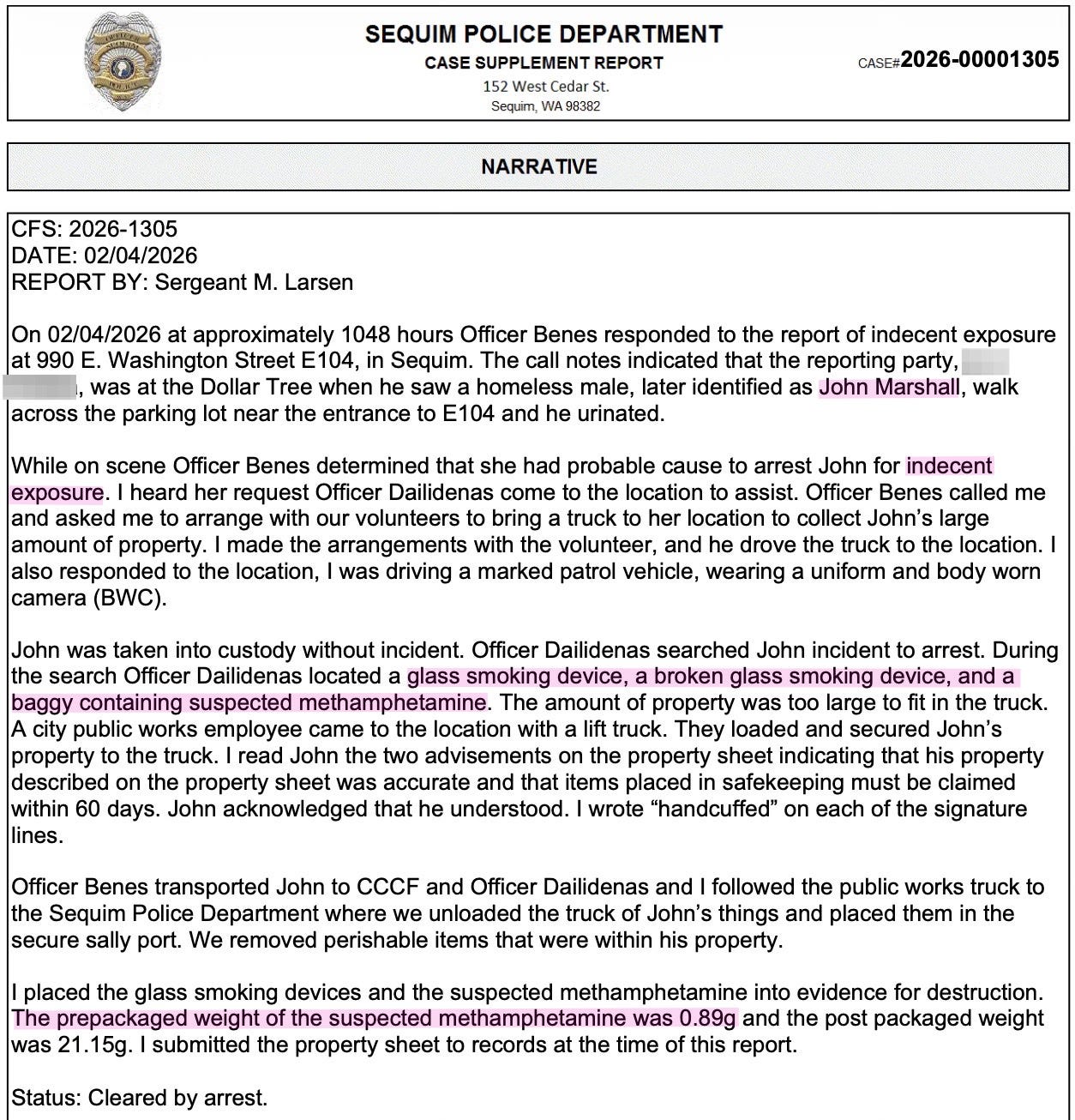

On February 4th, officers were dispatched to the Dollar Tree at 990 W. Washington Street in Sequim. A witness reported a man urinating in bushes with his genitals exposed in the parking lot.

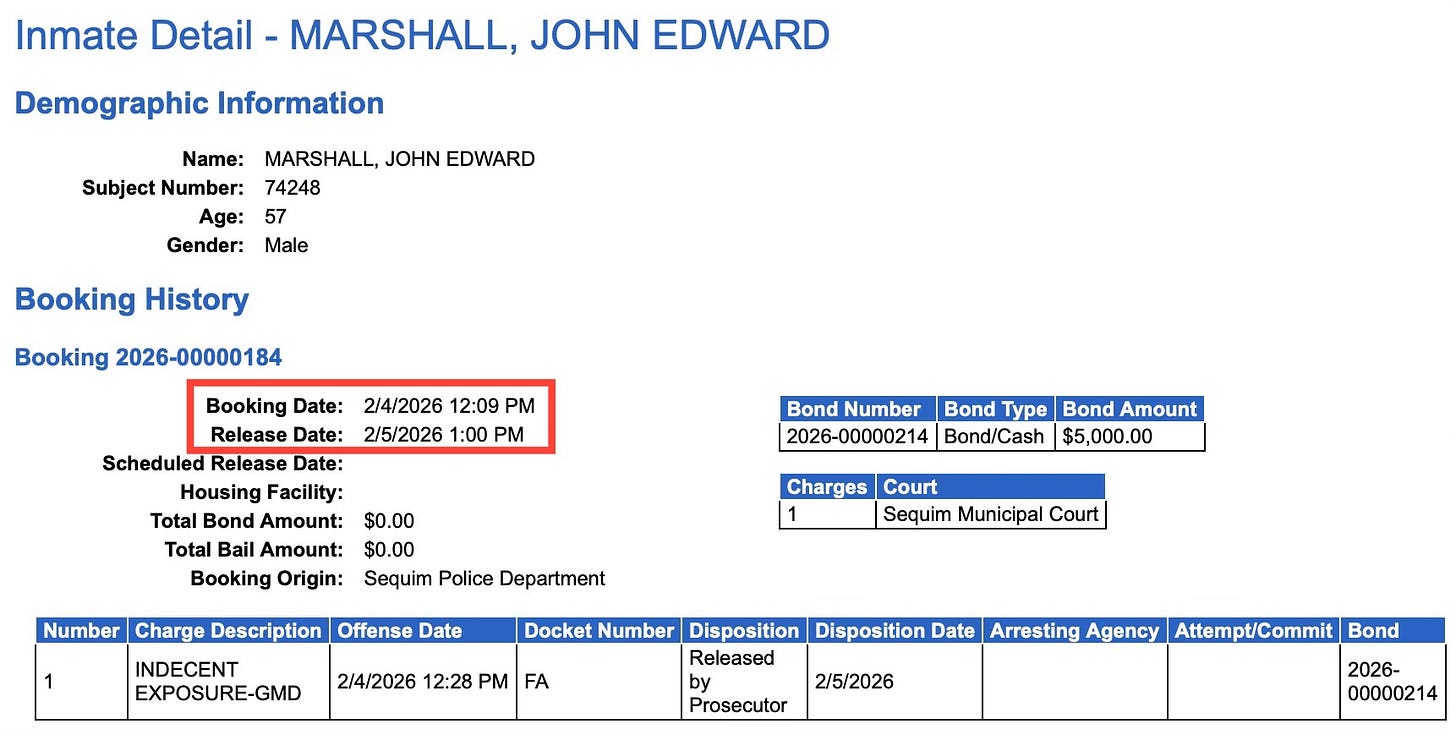

The suspect was identified as John E. Marshall.

According to the police report:

He was arrested for RCW 9A.88.010 – Indecent Exposure.

Officers located glass smoking devices.

A baggie containing suspected methamphetamine was found.

His property—two carts’ worth—required a city lift truck for transport.

Items were placed into safekeeping. Drug paraphernalia was logged for destruction.

Booking records show he was arrested on February 4th and released the next day.

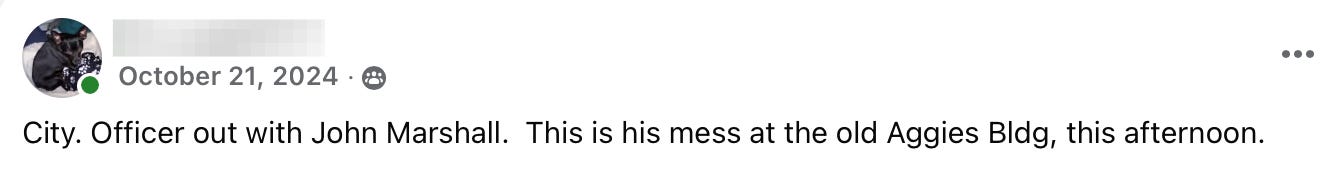

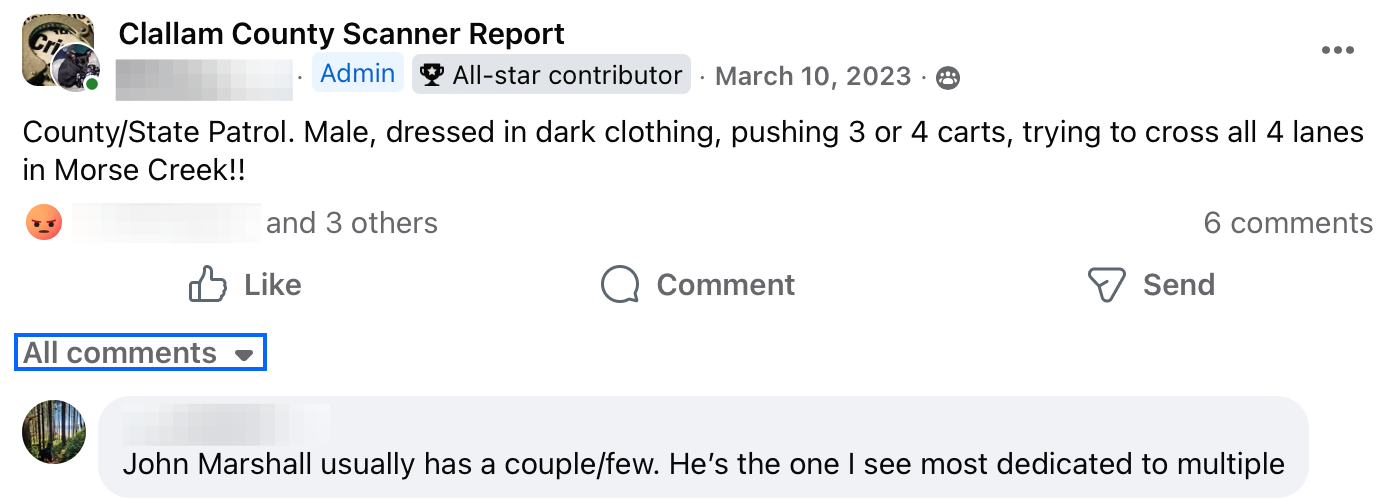

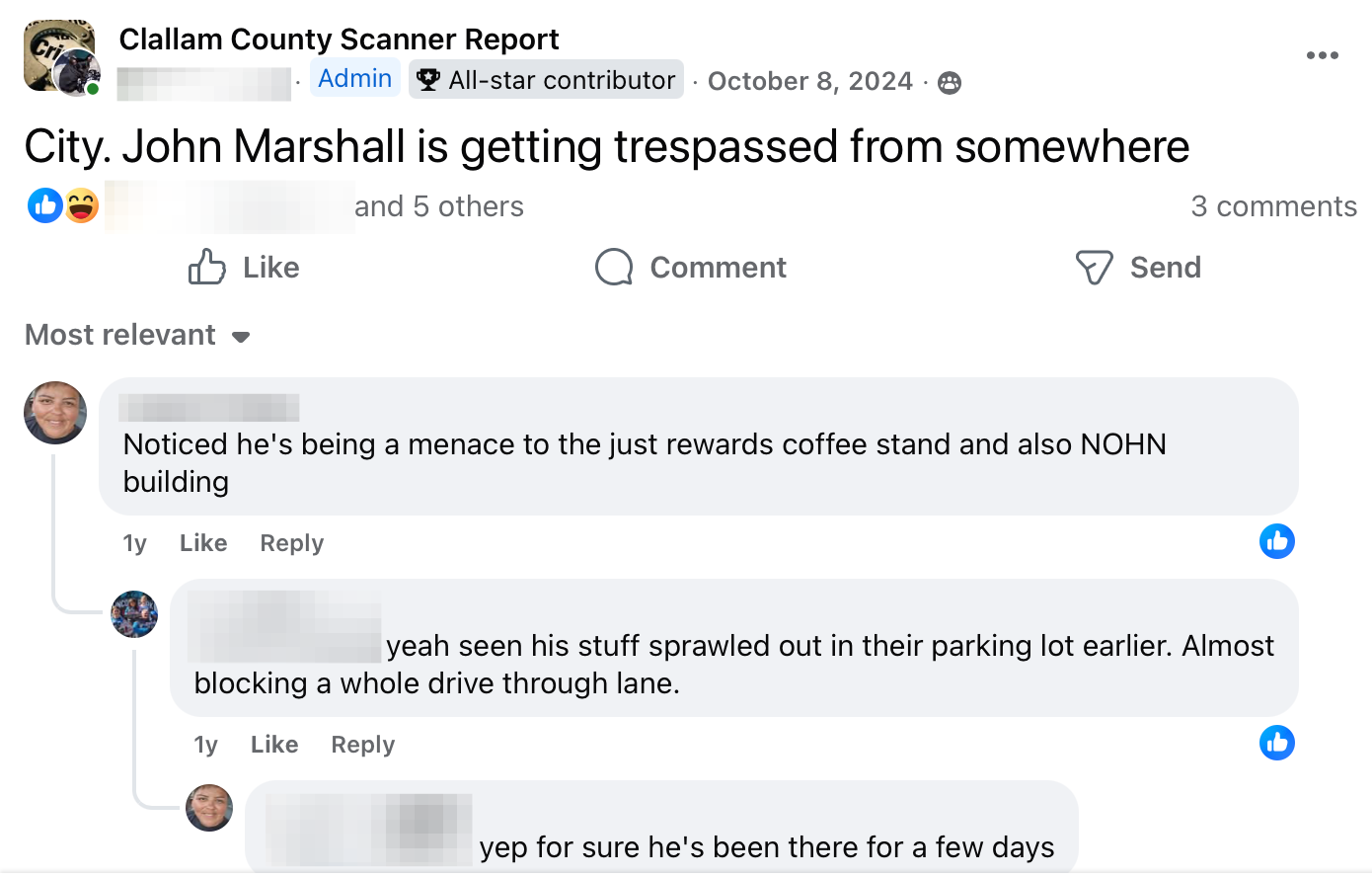

This wasn’t an isolated incident. Reports and social media posts spanning more than three years describe Marshall:

Crossing traffic with carts.

Yelling at residents downtown.

Being trespassed from parks.

Sleeping in commercial areas.

An engaged Watchdogger was in the QFC parking lot in Sequim and witnessed Marshall’s arrest earlier this month. Look closely at the City of Sequim Public Works truck piled with Marshall’s belongings.

A blue tarp, a wooden pallet, and couch cushions. The same items are shown in the photo below.

Weeks earlier, a parent wrote publicly that her son was expected to walk past an unstable man blocking sidewalks near 5th and Fir in Sequim. Police allegedly told the family to “take a different route.”

That encampment was:

Across from Peninsula Behavioral Health.

Half a block from the Boys & Girls Club.

One block from an elementary school.

Let that sink in.

A man arrested for indecent exposure and found with suspected methamphetamine had been sleeping on a sidewalk for days, a block from an elementary school.

And the official response is: reroute the kids.

The Hypocrisy of “Compassion”

Clallam County has poured millions into harm reduction infrastructure:

Housing-first initiatives.

Outreach contracts.

Public-health supply distribution.

Policies that deliberately deprioritize enforcement.

The promise was stability. Dignity. Better outcomes.

Instead:

Forks residents are picking up needles.

Sequim families are adjusting school routes.

The same individuals cycle through arrest, release, repeat.

Compassion has been redefined in Clallam County.

It no longer appears to mean protecting children, small business owners, or taxpayers.

It means protecting the policy.

When elected officials congratulate themselves on “progressive” solutions while residents organize volunteer cleanup crews and city crews haul carts with meth pipes into storage, something is broken.

This isn’t a failure of empathy.

It’s a failure of governance.

And residents across the county—Forks to Sequim—are documenting it themselves.

That’s Social Media Saturday.

Port Angeles City Councilmembers Drew Schawb, Jon Hamilton, and Amy Miller provided thoughtful, insightful responses to yesterday's question regarding Mark Hodgson's residency. Mayor Kate Dexter and Councilmembers LaTrisha Suggs, Mark Hodgson, and Navarra Carr did not reply.

Today's email is to the county commissioners. All three can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov.

Dear Commissioners,

Given that Marshall has reportedly been on the streets for over three years, was found with suspected meth and meth paraphernalia, was camping just a block from an elementary school, and was ultimately arrested for indecent exposure — how does the county define success for its harm-reduction policies? At what point do public safety concerns, especially when children are nearby, outweigh a hands-off approach?

Good Governance Daily Proverb:

In a system governed by law, crimes are defined by statute — not by sentiment.

Institutions protect trust by consistently and publicly enforcing clearly written rules.