Whatcom County is undergoing re-adjudication of water rights. Could Clallam County face a similar process? Here at home, a $41 million reservoir project, initially sold as a solution for salmon recovery and aquifer recharge, raises questions about water ownership. As the narrative shifts, the public is left wondering who will truly benefit. The battle for water could ultimately determine who controls the region’s future.

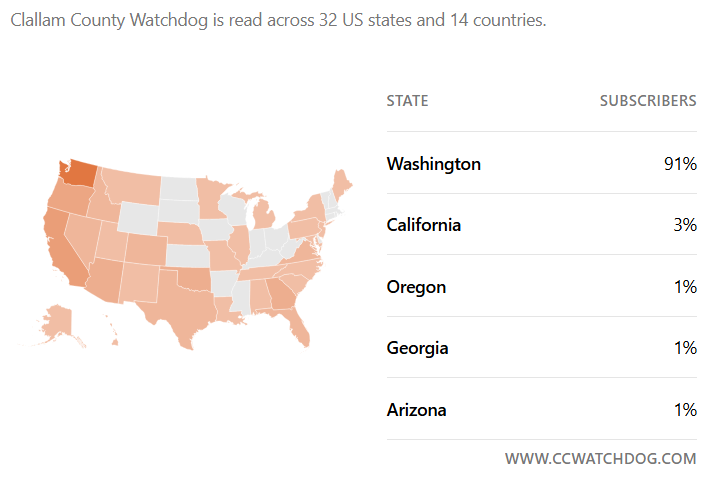

Substack, the platform that hosts Clallam County Watchdog, is full of fascinating data for creators. It tracks how many subscribers we have (2,424), how many sign up each month (154 on average), and how much monthly traffic the website gets (134,799 views). But the platform also shows the locations of our readers, which sparked some curiosity. Washington has the highest subscription rate, naturally. But why were people from 31 other states also tuning in?

Then, the messages started rolling in.

The answer is clear: people are researching possible retirement locations before they move to Clallam County from other parts of the country.

“We love it up there, but your articles are starting to get us concerned,” read a message from a married couple. One of them is retiring this year, the other can work remotely.

My usual reply has been, “I’m sure there’s always some backroom dealing and pulling the wool over the public’s eyes wherever you go. Don’t worry.”

But I have an update for you: now, it’s time to worry.

The Great Water Grab

From the Washington State Department of Ecology (DOE):

“Do you live in or near Whatcom County and do you use water from a well, stream, or lake? If so, you may be in the water adjudication area. Today, Ecology sent out claim forms by certified mail to 30,000 water users.

“When you fill out and submit a claim form, you will describe your past and current water use. Not filing can result in losing your right to legally use water in the future. If you receive a claim form, don’t throw it away and don’t ignore it.”

It’s a simple message. Fill out a 30-page claim form, detailing your water usage. Don’t file it, and you risk losing your right to water—forever. That’s right. Even if you use water from a private well, you still have to fill out the form.

What seems like a shocking government overreach feels oddly more acceptable after watching this DOE cartoon about losing your water rights.

The issue, however, isn’t just about securing rights for the Nooksack and Lummi Tribes, who are advocating for re-adjudication. It’s about the state reassessing ownership. Currently, the public owns the water, and residents, farmers, businesses, and tribes have all lived with the understanding that their water rights are protected. However, these rights are now being reexamined, and the stakes are significant.

By the conclusion of this reexamination of rights, every drop of water above and below ground in Whatcom County could potentially fall under the legal control of sovereign governments, like the Lummi and Nooksack Tribal Nations, that do not represent the majority of residents.

The drought that never ends

What does all of this mean for Sequim, a community in the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains where annual rainfall averages just 16 inches—half the amount of Whatcom County? The Dungeness Water Rule means private wells, (the ones not on sovereign land) are already being metered. The County, State, and even the Jamestown Tribe are planning for long-term water management, including the construction of a $41 million reservoir to store water for the community.

But it’s not just about water. This reservoir, situated atop earthquake fault lines and beneath high-voltage power lines, is a symbol of control—a control being sold as a tool for sustainability, aquifer recharge, and salmon recovery.

The messaging around the reservoir has largely focused on its salmon-saving capabilities, painting the project as an ecological boon for the community. But when you dig deeper, the promises have become less certain. The benefits are now downplayed as “possible.” The project that once promised a solution to water shortages has turned into a complex web of conflicting priorities, where each stakeholder has a different vision of who will own the water.

When you ask who owns the water in this new reservoir, the answers are as muddled as the politics behind it. Commissioner Mark Ozias says work is underway to determine ownership. Commissioner French claims it will be public. County Engineer Joe Donisi says the Highland Irrigation District will own it. The Jamestown Tribe’s Natural Resources Director, Hansi Hals, suggests the Tribe might have a share. Meanwhile, irrigators say the Department of Ecology will grant permission for the Highland Irrigation District to use the water, but they’re unclear on who truly owns it.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter who owns it today. The more pressing question is: who will own it after the possible re-adjudication of water rights?

Fitting a square peg into a round hole

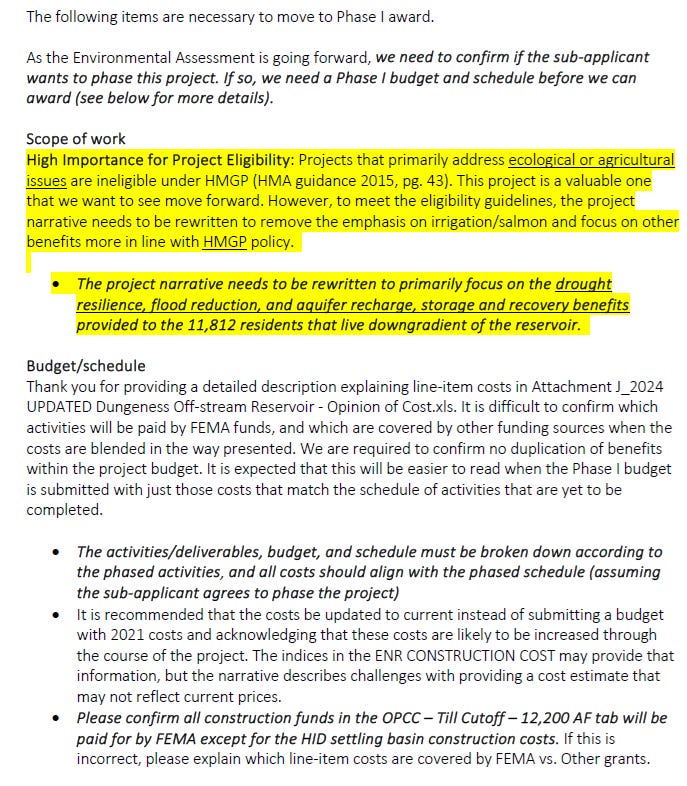

A document sent to the County on June 18, 2024, has surfaced. It’s from the Washington State Emergency Management Division (WAEMD) and reveals an intriguing twist in the story of the reservoir: FEMA is currently reviewing a $30 million grant request to fund the majority of the project. However, to meet FEMA’s guidelines, the county must reframe the narrative.

The document states:

High Importance for Project Eligibility: Projects that primarily address ecological or agricultural issues are ineligible under HMGP (HMA guidance 2015, pg. 43). This project is a valuable one that we want to see move forward. However, to meet the eligibility guidelines, the project narrative needs to be rewritten to remove the emphasis on irrigation/salmon and focus on other benefits more in line with HMGP policy.

• The project narrative needs to be rewritten to primarily focus on the drought resilience, flood reduction, and aquifer recharge, storage and recovery benefits provided to the 11,812 residents that live downgradient of the reservoir.

Ecological and agricultural concerns, which the project was initially sold on, aren’t eligible for FEMA funding. The project narrative needs to be rewritten to focus on drought resilience, flood reduction, and aquifer recharge for the 11,812 residents living downstream of the proposed reservoir. In short, the county wants the money, but it needs to repackage the project to make it fit FEMA’s mold.

Who should be overseeing the reservoir?

The Clallam County Charter clearly states that the Director of Community Development (DCD) is responsible for administering watershed planning.

Yet, Deputy Director of Public Works Steve Gray has been managing the reservoir project. Elected DCD Director Bruce Emery has been noticeably absent from briefings and the open house. When asked why Public Works—not the DCD—is leading the project, the commissioners’ responses were evasive:

Commissioner Ozias: “The current Department of Community Development, I don’t believe, has felt to a large extent like they’ve had the bandwidth to participate in leadership in that project.”

Commissioner French: “Where there is a County nexus to watershed management, I do think the Department of Community Development has a reasonable nexus to that.” (Yet, no explanation as to why the DCD is not in charge.)

Commissioner Johnson did not comment.

This isn’t just bureaucratic reshuffling—it’s a deliberate shift of power. The DCD Director is elected and accountable to the voters. The Deputy Director of Public Works is appointed, meaning their accountability lies with the commissioners—not the public. The Clallam County Charter doesn’t say, “unless the DCD is too busy” or “unless the commissioners prefer otherwise.”

Ignoring the charter and placing reservoir management under Public Works instead of the DCD is a direct violation of the governing document created by the people of this county.

The true wealth of water

The County continues to advance the reservoir project despite uncertainty regarding future funding for its maintenance and operations. In its current vision, it will be a $41 million pond designed to irrigate crops on one side of the Dungeness River during the last 30 days of summer.

This is about more than just water—it’s about power. Control over water means control over land use, development, agriculture, and ultimately, the region’s economic and political future.

The reservoir’s purpose shifts depending on who is writing the checks. First, it was for salmon and aquifer recharge. Now, it’s about drought resilience. What will it be next? The county’s evolving narrative suggests one thing: this is about consolidating control over the region’s most valuable resource.

As Clallam County inches toward potential re-adjudication, the true power struggle is becoming clear:

Who gets access to water?

Who makes those decisions?

And ultimately, who will control the future of Clallam County?

The reservoir is more than just a body of water. It’s a chess piece in a larger game. And if the public doesn’t start paying attention, they may wake up to find the rules have changed—and they’re on the losing side.

Excellent update, Jeff. How many times can an entity reapply for a grant? FEMA is a mess right now. I am curious what will happen if the grant is stalled, only partial funded, or completely denied. (Remember the Recompete Grant that was only partially funded?) Last night's CRC "Town Hall" was very well attended. For all Watchdoggers, Commissioner Jeff was willing to answer any questions from the audience. Most other attending commissioners did not want any form of q & a. However, what was telling was the prepared comments from proponents for a water steward, which is the next step to accomplishing the reservoir project's green light. The next CRC Towm Hall is April 1. Another chance to voice opinions and concerns and maybe this time get some answers.

Great investigative reporting Jeff.

The thorn in the reservoir and water conservation side has always been the Jimmycomelately project. At that project they decided how to build the best salmon, floodplain, estuary restoration system that used the least amount of water. Every aspect of creek and river management had been decided in 2003 based upon science from 1970-2001. Every aspect. One of the lead entitles, Clallam Conservation District hired an engineer to chime in from the water conservation side. Randy Johnson of Jamestown Tribe, oh ye of Worthington's a "crackpot" fame, was also one of the creators of the Jimmycomelately science.

Jimmycomelately science:

Eliminate tributaries and re-channeling possibilities. WHY? To conserve water and prevent bed scour caused by re-channeling events.

Baffles:

Filter big gravel from river to allow more fine silt to gather in slower moving water in the fixed meandering sections of the river or creek.

Fixed meandering channels at 3 percent grade:

They built a switchback that never was intended to re-channel, with deep channels that gradually reduced the grade of the river and slowed the water down.

No salmon hotel logs in the fixed meandering parts of the river:

Jimmycomelately project engineers decided the salmon hotel logs washed out the beds after the flood and wanted a natural erosion process away from the fixed meandering sections to avoid the re-channeling and decided not to use an engineered log jam.

Then, after the Jimmycomelately project they threw all of that "science" out the window when they started managing the Dungeness. Worthington the "crackpot" tried to get Randy Johnson to acknowledge the Jimmycomelately science on a webinar, and he went into a coughing fit the rest of the webinar. Later he wrote the "crackpot" email to Kathy Lear of DRMT his partner in crime for altering the Jimmycomelately science.

They are using every tool they have to justify changing the Jimmycomelately science in order to achieve a political outcome. They sacrificed water, farming, property rights and salmon spawning and now they want to hire a "hydrologist" to justify changing what they already decided works best for every aspect.

Is the Jamestown tribe going to dismantle the old Jimmycomelately project based on what this new science will tell us?

Not on your life.