A Harm Reduction Photo Tour

Behind the talking points, a resident documents what Port Angeles is actually living with

These photos were taken by a Port Angeles resident on a routine Saturday morning walk through downtown. She asked to remain anonymous, but wanted the record to be public. What she captured isn’t dramatic or unusual—it’s ordinary. The same locations, the same behaviors, the same debris, over and over again. County and city leaders describe current drug policy as compassionate and effective. These images show what that looks like on the ground, and who ends up living with the consequences.

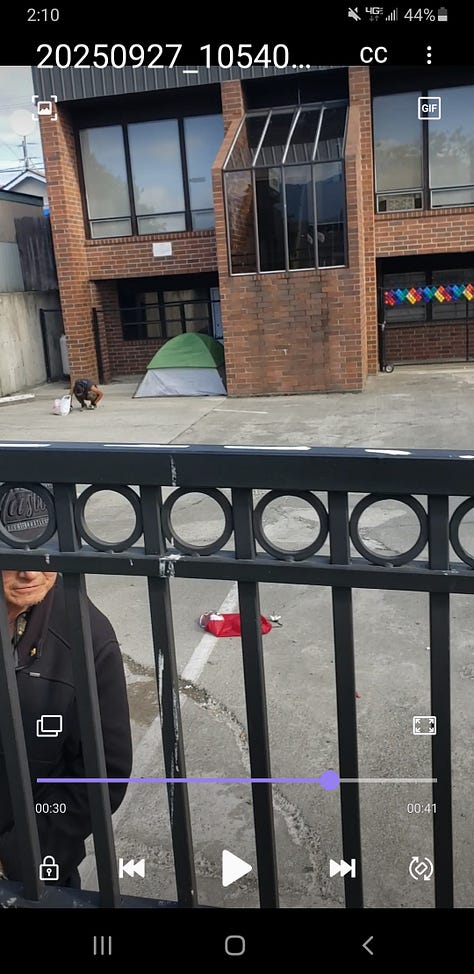

A familiar corridor

The area near the 3rd Street Health Department, the Lincoln Street Safeway, and the orange house behind Safeway has been a known drug activity zone for years. Anyone who has worked as an EMT or patrol officer in Port Angeles since 2020 knows how often overdoses happen here, or within just a few feet of it.

The back wall of Safeway has been repainted again and again. It gets patched and repainted multiple times a year because of tagging and damage caused by people leaning against it to defecate. The clean coat of paint never lasts.

What gets left behind

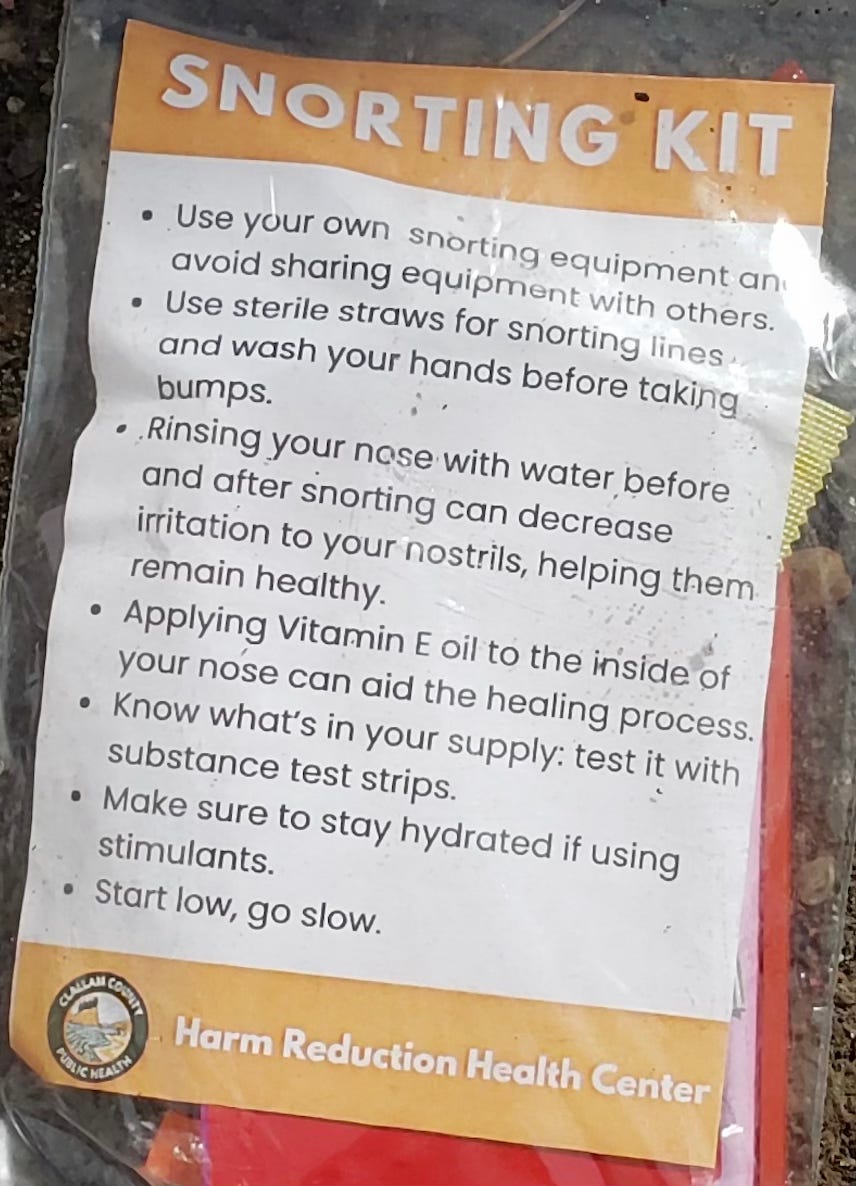

Behind Safeway, the ground is littered with items from the Clallam County Health Department’s harm-reduction program. Pipes. Gloves. Snorting kits. Foil used to smoke fentanyl.

These aren’t random items. They match the program’s own supply list.

The snorting kits include printed instructions reminding users to wash their hands, rinse their noses before and after using drugs to avoid irritation, apply vitamin E oil to help with healing, stay hydrated, and to “start low, go slow.”

This is all taxpayer-funded.

Pipes and cleaning kits

Photos show foil, a glass pipe, and a county-funded pipe-cleaning kit. The glass “hammer” pipe is one of several types of narcotics pipes distributed by public health. It was carefully wrapped in foam padding.

“Bubble” and “straight” pipe styles are also available, along with free pipe-cleaning brushes.

These items don’t disappear. They end up on sidewalks, in parking lots, in parks, and washed down our streams.

Theft and meth-driven behavior

One photo shows a plug with cut wire. Anything with wire left outside—appliances on porches, a lamp in an unlocked shed, tools—will be stripped. It’s common to find piles of partially stripped wire in abandoned camps. Some of it is for scrap. Some of it is simply meth-driven behavior.

Walking downtown on a Saturday

On a Saturday walk through Port Angeles, the photographer saw people staggering through the Health Department parking lot.

People were also using an umbrella as a windbreak to smoke behind the Veterans’ Park bell.

In the city parking lot on Lincoln, which is supposed to serve downtown businesses, someone was rearranging branches and digging.

In several photos, someone in the background is crouched, scanning the ground and picking up tiny objects. The same behavior was seen hours apart, and again at Veterans’ Park. This is known as meth punding.

Punding isn’t quirky or harmless. It’s a common side effect of long-term meth use, and once you’ve seen it, you start to recognize it everywhere. People get locked into repetitive, meaningless tasks—scanning the ground, picking at dirt or gravel, pulling apart objects, or collecting bits of trash as if they’re valuable. They can stay like that for hours, barely aware of what’s happening around them. It often goes hand in hand with days of little or no sleep. Over time, it turns into digging up landscaping, tearing at concrete, stripping wire, or dismantling bikes and anything else within reach. When you see punding happening in parks and parking lots, it’s a visible sign of heavy stimulant use—and a reminder that the damage isn’t abstract. It shows up in the ground itself, and in the public spaces everyone else is expected to share.

Behind Veterans’ Park, umbrellas were up while people stared at the ground. Others pulled up grass and branches, piling them on top of bike parts. One person sat upright with a blanket over their head, a common way to block the wind while smoking drugs, before passing out.

Businesses absorb the impact

Some photos show people using a public parking lot reserved for downtown businesses to “hit and crash” — meaning, use drugs before passing out.

Across the street is a small business owned by an Asian American woman. This is what policy looks like at her front door. Where is the equity for business owners expected to operate under these conditions?

Disperse, then return

An officer arrived at Veterans’ Park. The group cleared out quickly.

Minutes later, they regrouped at Safeway and resumed aggressive panhandling.

Panhandlers blocked the right-hand exit lane. Drivers had to cross into oncoming traffic to get around them.

Cleanup without change

A free food truck parks near Safeway at 4th and Laurel several times a week. Volunteers—often from 4PA—regularly clean the area. The mess always comes back.

The cleanup is appreciated. The cycle never ends.

Vandalism climbs higher

Even the upper parts of downtown buildings aren’t spared. From the top of the Oak Street zigzag ramp, tagging is visible high above street level.

Tagging isn’t art. It’s destruction.

As the photographer put it plainly: “This is Mike French’s PA.”

Under the zigzag

Under the Oak Street zigzag ramp is another regular drug-use site. People dig into the dirt and concrete, smoke meth and fentanyl, and leave foil behind. The photos show exposed concrete footings damaged by repeated digging and erosion.

This is long-term damage, not just litter.

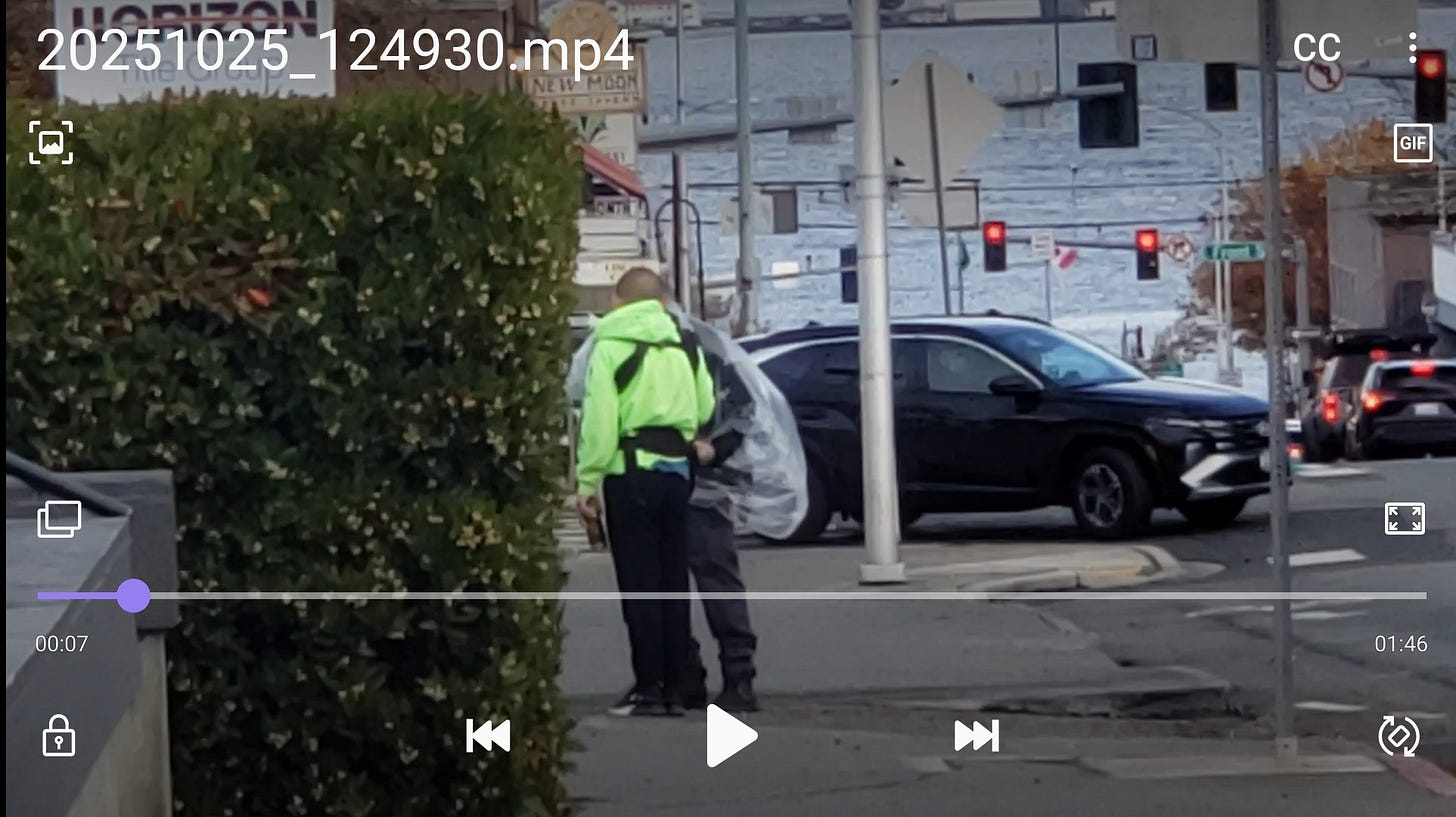

Open-air dealing

Back at the Safeway entrance, people panhandle and receive drug deliveries without moving. A dealer arrives on a small motorcycle and sells openly.

One photo shows a man in a high-visibility shirt connected to a group camping on the Title Company porch on Lincoln. Another person walks behind the Veteran’s Park bell, returns, and completes a hand-to-hand exchange on the sidewalk.

Why these photos matter

These images aren’t anti-compassion. They are evidence.

They show what happens when policies are measured by supplies distributed instead of harm reduced—when impacts are shifted onto neighborhoods, parks, small businesses, and anyone who happens to live nearby.

We thank the Port Angeles resident who took these photos, who cares enough about her community to document what she sees, and who shared them so this can’t be dismissed as exaggeration or rhetoric.

This is what’s happening. Every day.

A way forward

Compassion and accountability are not opposites. If current harm-reduction strategies are working, the public should be able to see that clearly and locally.

That starts with:

Reporting outcomes, not just services provided—changes in public drug use, litter, vandalism, and overdoses.

Setting real boundaries so parks, business parking lots, and sidewalks aren’t treated as acceptable drug-use zones.

Acknowledging and measuring impacts on nearby residents and small businesses, especially downtown.

An independent review of whether distributing smoking and snorting supplies is actually reducing harm—or simply relocating it.

Residents aren’t asking for miracles. They’re asking for honesty, balance, and policies that don’t ask the same neighborhoods to absorb the damage indefinitely.

The commissioners did not reply to yesterday's email. Here is the question asked today:

Dear Commissioners,

The article calls for reporting on impacts on parks, litter, vandalism, and nearby residents, not just services provided. Will the County commit to publishing quarterly impact reports with both positive and negative indicators of harm-reduction outcomes, and if so, what metrics would you include?

All three commissioners (who fund the Harm Reduction Health Center) can be reached by contacting the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov

Thank you for taking the time to document and share this, Anonymous. The delivery motorcycle is routinely parked next to Tumwater Creek, near the bridge off the truck route (on County-owned land). Local residents see what’s going on. Unfortunately, our leaders continue to look the other way while funding policies that perpetuate our local drug haven.